Introduction

We spent some time debating whether to visit this historic city, one so deeply marked by an irreversible past. In the end, we chose to go — and Hiroshima left a profound impression on us. It stands as both a guardian of memory and a powerful symbol of peace.

Walking through its memorials, we were often struck by moments of sadness and disbelief at the horrors that once unfolded here. It was an emotional experience — one that reminded us, painfully, how the senselessness of war still lingers in many parts of the world today.

Despite everything we’ve learned from history, the destruction, the suffering, the loss — it continues. And so do the headlines.

Hiroshima Before the Bomb

Before it became known worldwide for the tragic events of 1945, Hiroshima had a long and layered history. The city was founded in 1589 by the feudal lord Mōri Terumoto and originally developed around a central castle, like many Japanese cities of the time.

During the Edo period (1603–1868), under the Asano clan, Hiroshima grew into a steady administrative and commercial center. The city continued to evolve through the Meiji era (1868–1912), becoming progressively industrialized and home to various sectors, including textiles, shipbuilding, weapons manufacturing, and food processing.

Its port at Ujina became strategically important, and Hiroshima played an active role during the Sino-Japanese War (1894) and the Russo-Japanese War (1904). By 1945, the city had a population of about 350,000 and was considered one of the main urban centers in western Japan.

The event / Boom!

On August 6, 1945, at 8:15 a.m., life in Hiroshima changed in an instant. Until then, the city had been largely spared from the heavy bombing that had devastated other major Japanese cities. That morning, however, it became the target of the American bomber Enola Gay, which dropped the first atomic bomb ever used against civilians — nicknamed Little Boy.

The explosion occurred about 600 meters above the city center, instantly flattening nearly everything within a two-kilometer radius. Around 75,000 people died in the blast within seconds. In the days that followed, thousands more would succumb to their injuries or radiation exposure, often in severe suffering. By the end of 1945, an estimated 140,000 people had lost their lives as a result.

Out of the city’s 90,000 buildings, approximately 62,000 were destroyed. One of the few structures that remained standing, though severely damaged, was the Genbaku Dome — the charred remains of the former Industrial Promotion Hall. Today, it stands as a global symbol of the devastating impact of nuclear weapons.

Aftermath

Today, 80 years after the bombing, we can begin to grasp the scale of the devastation thanks to survivor testimonies and preserved memorial sites. Yet the pain and intensity of the tragedy can truly only be understood by those who lived through it. What Hiroshima endured defies imagination. No one should ever have to experience such horror. Even the photographs — frozen moments in time — only hint at the shock and suffering. Seeing them is already difficult; living through it would have been unbearable. The city has since been completely rebuilt, blending modern architecture with deep respect for its past. While Hiroshima has embraced a contemporary style, landmarks like Hiroshima Castle and the Shukkeien Garden have been restored to their original appearance. A large area of remembrance — the Peace Memorial Park — now stretches from the Peace Museum to the Genbaku Dome, one of the few structures that partially withstood the blast and has since become an enduring symbol.

In 1949, a major reconstruction effort began, and Hiroshima was officially declared a City of Peace by the Japanese government. With support from across Japan and the international community, the city has become a global symbol of remembrance, resilience, and the call to eliminate nuclear weapons. Today, over one million people live here, and each year millions of visitors come to pay tribute to the victims and reflect on the future.

____

Must-See Sites in Hiroshima:

Peace Memorial Park

A powerful space dedicated to the memory of the atomic bomb victims and to the global message of peace. Key monuments include:

- Peace Memorial Museum:

The Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum chronicles the devastating impact of the atomic bombing on Hiroshima, presenting harrowing artifacts and testimonies to educate visitors on the horrors of nuclear war and advocate for lasting world peace.

- Genbaku Dome (Atomic Bomb Dome):

This partially intact structure, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, stands as a stark reminder of nuclear destruction.

- Peace Memorial Museum:

A deeply moving museum that recounts the events of August 6, 1945, through survivor stories, photographs, and personal belongings.

- Flame of Peace:

Lit in 1964, the flame will remain burning until all nuclear weapons are eliminated.

- Cenotaph for the A-Bomb Victims:

An arched monument honoring all those who lost their lives in the bombing.

- Peace Bell and Children’s Peace Monument:

Touching tributes, especially to Sadako Sasaki and the many young lives lost.

Hiroshima Castle (Rijō):

Rebuilt after the war, this traditional wooden castle is surrounded by a scenic moat and park. It now houses a museum dedicated to samurai history and the evolution of the city.

Hiroshima Castle: Between Feudal Heritage and Modern Resilience

Hiroshima Castle — also known as Rijō, or the “Carp Castle” — is one of the city’s most iconic historical landmarks. Originally built in 1589 by the feudal lord Mōri Terumoto, it marked Hiroshima’s rise as a regional military and political center. For nearly 300 years, the castle served as the seat of successive daimyō lords from the Mōri, Fukushima, and Asano clans.

Constructed on flat land and surrounded by wide moats, the five-story castle stood 26.6 meters high atop a 12.4-meter stone base. It served both as a noble residence and a strategic observation post. This symbolic height has been faithfully preserved in its modern reconstruction. During the Edo period, the castle remained a significant center of power until Japan’s feudal system ended with the Meiji era.

On August 6, 1945, the castle was completely destroyed by the atomic bomb. Only the stone foundations and a few remnants of the site survived. The main keep was rebuilt in 1958 using reinforced concrete, and wooden elements were added in the 1990s to restore its traditional appearance.

Today, the castle houses a museum focused on the region’s feudal history, the samurai culture, and Hiroshima’s urban development before 1945. Exhibits include scale models, suits of armor, swords, and more. From the panoramic viewing deck on the fifth floor, visitors can enjoy a 360-degree view of the city.

The castle’s nickname, “Carp Castle,” comes from the dark color of its outer walls, said to resemble carp scales. Its surrounding park offers a peaceful setting, especially popular for walks in spring when the cherry blossoms are in full bloom.

The grounds also quietly tell a story of resilience — a eucalyptus, a willow, and a holly tree that survived the bombing still stand near the hypocenter, living symbols of endurance and renewal.

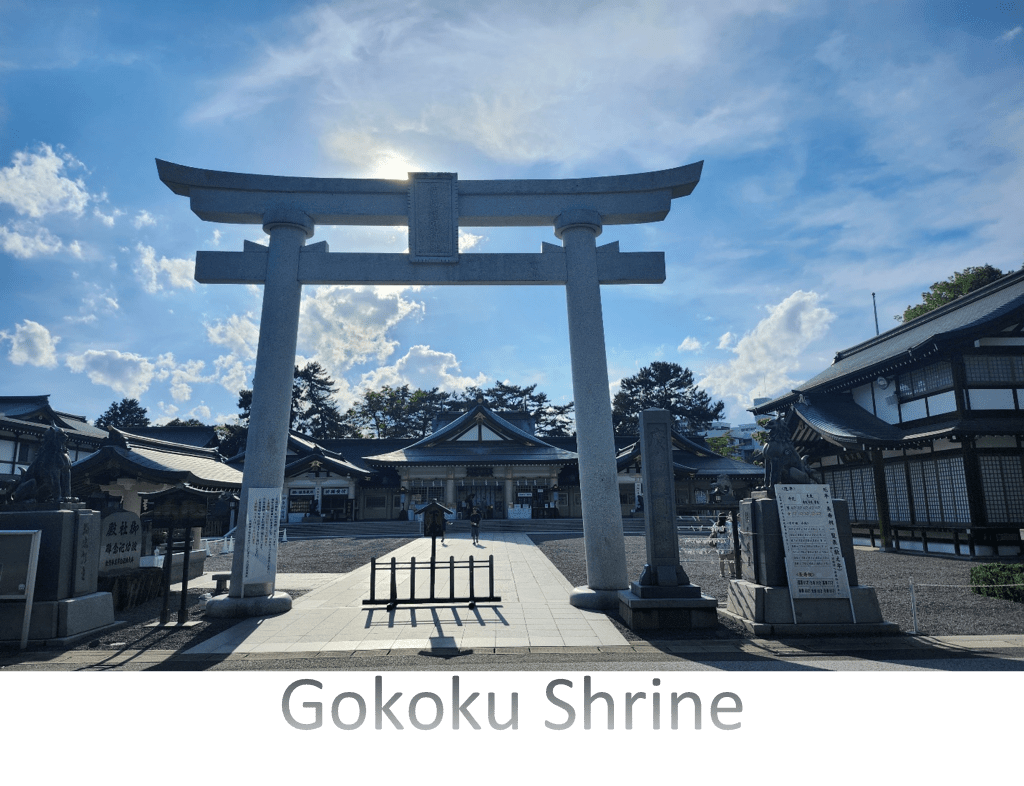

Hiroshima Gokoku Shrine

The Hiroshima Gokoku Shrine was founded in 1869, the first year of the Meiji era, in the Futabanosato district of Hiroshima. It was built to honor the members of Hiroshima’s feudal domain (han) who lost their lives during the Boshin War.

In 1934, the shrine was dismantled and moved to its current location. Five years later, in 1939, it was renamed Hiroshima Gokoku Shrine (Gokoku literally means “protect the country”), a name shared by several other shrines across Japan dedicated to the souls of soldiers who died in service to the nation.

The shrine was completely destroyed in the 1945 atomic bombing. It was later rebuilt in 1965 on the grounds of Hiroshima Castle, thanks to donations from the people of the city.

Today, the Hiroshima Gokoku Shrine remains an important spiritual site for the local community. It is one of the most visited places in the city, particularly for the New Year tradition of Hatsumōde (the first shrine visit of the year) and Shichi-Go-San, a traditional celebration for children aged 3, 5, and 7.

Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park

The Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park is an iconic site located in the heart of the city, dedicated to the memory of the victims of the atomic bombing on August 6, 1945. Established after the war, the park’s mission is to ensure that the horrors of the past are never forgotten, while also conveying a powerful message of peace.

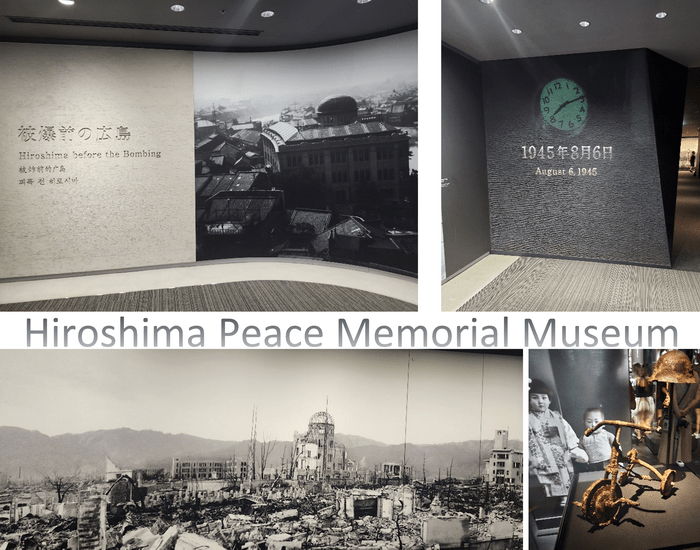

Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum

Located at the heart of the Peace Memorial Park, the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, founded in 1955, is an essential stop for understanding the tragedy of August 6, 1945. This poignant and immersive museum offers crucial insight into the events of that day, placing them within their historical, geographical, and human context.

The museum’s exhibits provide a detailed look at the city before the bombing, the challenges of World War II, and the immediate and long-term consequences of the nuclear attack. Through heartbreaking survivor testimonies, personal items – such as burned clothing or a tricycle deformed by the heat – and numerous photographs, visitors gain an understanding of the scale of destruction and the suffering experienced in a landscape left in ruins, devoid of landmarks or resources.

Recommended visit time: Approximately 2 hours.

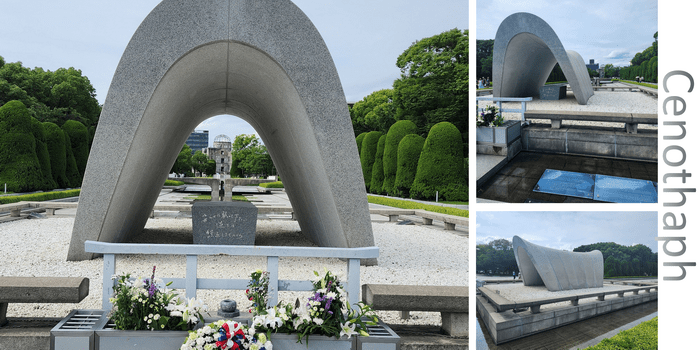

The Cenotaph for the Atomic Bomb Victims

Located at the heart of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, the Cenotaph is a granite arch designed by architect Kenzō Tange. Inaugurated in 1952, shortly after the end of the American occupation, it was unveiled to the public by children orphaned by the bombing. Originally made of stone, the arch was renovated with granite in 1985 due to the degradation of the stone over time. Officially named the Hiroshima Memorial Stele, City of Peace, the Cenotaph shelters beneath its arch a symbolic tomb containing 59 volumes listing the names of the victims of the nuclear attack.

The arch represents a protective shelter, a place for reflection, and also a call for peace. The Cenotaph is carefully aligned with the Peace Flame and the Atomic Bomb Dome, creating a powerful axis of memory.

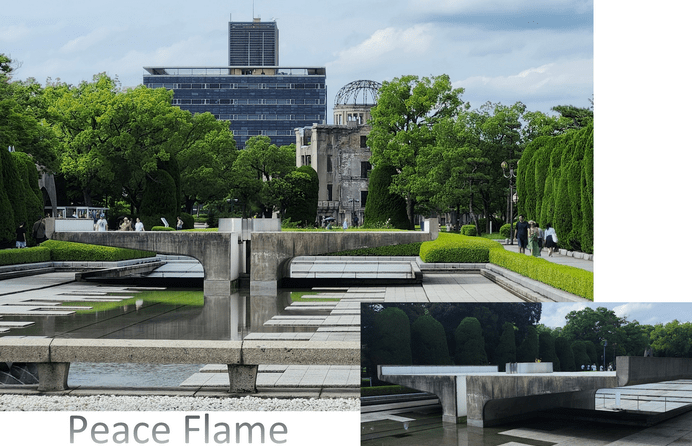

The Peace Flame

Lit on August 1, 1964, the Peace Flame has been burning continuously at the heart of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park. Designed by architect Kenzo Tange, it rests on a symbolic pedestal representing tightly clasped wrists and open palms reaching toward the sky, in tribute to the victims who, after the explosion, desperately sought water.

This flame embodies Hiroshima’s commitment to the abolition of nuclear weapons. It will continue to burn until the day all nuclear weapons have disappeared from the surface of the Earth. Over time, it has become a powerful symbol of peace and hope, serving as the light for various events, including the 1994 Hiroshima Asian Games. Its message remains clear: a peaceful future for all generations.

Children’s Peace Monument

The Children’s Peace Memorial, located in the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, honors the children who were victims of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. The monument is most famously known for the statue of Sadako Sasaki, a young girl exposed to the bomb’s radiation, who became a symbol of the fight against nuclear weapons. Diagnosed with leukemia, she began folding 1,000 paper cranes, following a Japanese legend that says doing so would grant one’s wish for healing. After her death, her friends organized a fundraising campaign to build a memorial in her honor and for all the young victims, both direct and indirect, of the bombing. The memorial was funded by children from over 3,100 schools in Japan and abroad. The inscription beneath the statue reads: “This is our cry, this is our prayer for building peace in the world.”

The 9-meter-high monument is topped with a bronze statue of a young girl holding a golden paper crane above her head, symbolizing hope and peace. Surrounding the monument are display cases containing hundreds of paper cranes, a poignant tribute to Sadako’s legacy and the enduring desire for global peace.

The Peace Bell – A Global Call for Peace

Inaugurated in 1964 near the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, the bronze Peace Bell symbolizes a prayer for global peace and honors the victims of the atomic bombing. Engraved with the words “May Peace Prevail on Earth,” it serves as an invitation to reflect on the suffering caused by war and the importance of preserving peace.

What makes it unique is that visitors are invited to ring the bell, thereby participating in a symbolic act of solidarity, remembrance, and hope. Every year, people from around the world come to strike the bell, expressing their commitment to a peaceful future and uniting nations in the fight against nuclear weapons.

The Hiroshima Dome – A Witness Frozen in Time

The Atomic Bomb Dome (Genbaku Dôme) stands as the iconic remnant of the nuclear explosion that struck Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. Designed in 1915 by architect Jan Letzel, this building originally served as an exhibition hall to promote local industries. Located near the epicenter of the explosion, the structure is one of the few buildings that partially survived the blast, becoming a poignant symbol of both destruction and resilience.

After the war, the people of Hiroshima decided to preserve it in its ruined state as a memorial—a frozen image of the devastation caused by the bomb. Inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1996, the Dome now stands in the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, providing a place for reflection on peace.

Statue of Mother and Child in the Storm

The Mother and Child in the Storm statue, created by sculptor Shin Hongo, was gifted to Hiroshima in 1959 during the fifth World Conference Against Atomic Bombs. Funded by a fundraising campaign led by the women of the city, it was cast in bronze and installed in 1960 in front of the Prayer Fountain.

Prayer Fountain or Peace Fountain

The Prayer Fountain is much more than an ornamental basin; it represents a tragic and deeply human moment in Hiroshima’s history. After the explosion of the atomic bomb, many survivors, severely burned and parched, desperately sought water. When radioactive black rain fell on the city, some tried to collect the drops, unaware that they were contaminated and deadly. This fountain was built by the Hiroshima Bank and gifted to the city in 1964, in memory of those victims who perished while searching for water.

Other Monuments

Throughout the city, numerous monuments honor the victims of the Hiroshima bombing. There are dozens of steles, gravestones, and commemorative plaques dedicated to specific groups: healthcare workers, teachers, municipal employees, military personnel, victims of Korean descent, electricity distributors, postal workers, bank employees, and more.

These memorials, spread across the city and within the Peace Memorial Park, serve as reminders of the immense human loss and the diversity of lives affected. Each monument encourages visitors to reflect on the consequences of war and the importance of building a peaceful future.

Hiroshima has become an international symbol of peace. Among the survivors of the August 6, 1945 bombing, there are 161 trees. These trees, known as hibakujumoku, stand as testimony to both the destruction endured and the resilience of nature in its ability to regenerate.

Hiroshima Museum of Art

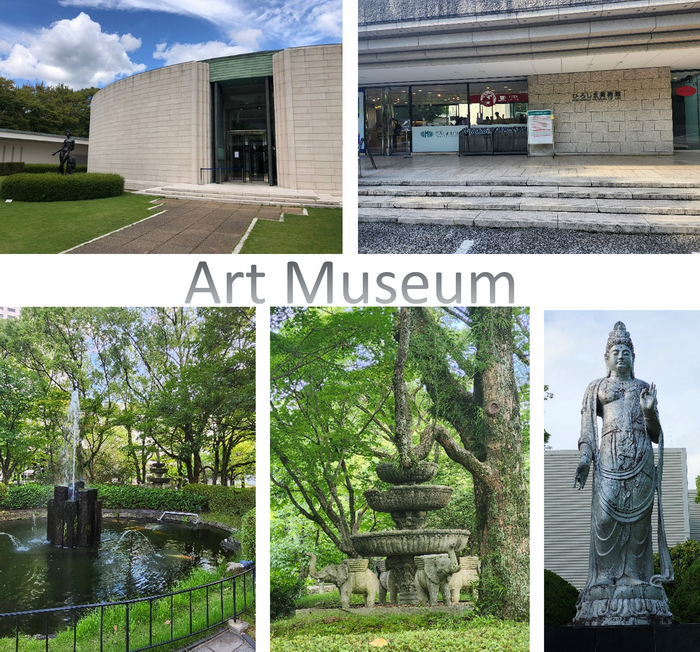

While visiting an art museum in Hiroshima may not have been our initial priority, the Hiroshima Museum of Art surprises with the quality of its collection. Its building, designed around the theme of “Love and Peace,” features a circular hall inspired by the Atomic Bomb Dome.

Things to see around the museum:

- Statue of the Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara – A symbol of compassion and peace.

- Maronie Fountain (マロニー噴水) – Surrounded by horse chestnut trees, this fountain features an Indian horse chestnut tree, gifted in 1980 by Claude Picasso, the son of Pablo Picasso, to mark the opening of the museum. Nishikigoi carp swim peacefully in the water.

- Elephant Fountain (象の噴水) – A playful elephant-shaped fountain, particularly beloved by families.

“Morning” Statue

At the Shinkansen exit of the JR Hiroshima Station, you will find a gilded bronze sculpture titled Morning. Created by sculptor Entsuba Katsuzō (1905–2003), this piece depicts a boy playing the trumpet, accompanied by two women dancing. Installed in 1979 to celebrate the inauguration of the Sanyō Shinkansen line to Hiroshima, the sculpture symbolizes the city’s progress and hope.